Concierge ABA

Eliminating Echoic Interference: The Clumsy Echoic

As clinicians, it is incumbent on us to use the best tools available for the kinds of problems we are tasked to solve. Similarly, it is our responsibility to recognize the limitations of those tools. The focus of this discussion will be on the use of a common tool, standard echoic training (SET), in autism intervention for children with language delays; its benefits and limitations. SET is most closely associated with what is commonly referred to the Applied Verbal Behavior (AVB) or Verbal Behavior (VB). (Burke, C., 2011, Carbone,V. 2001). Concerning SET, Shane (2016) writes,

“Standard echoic or vocal imitation training involves presenting a vocal model, and providing access to reinforcers if the participant imitates that model within an established amount of time. This is a relatively simply procedure that is easy to implement.”

It looks like this:

Teacher says “Ah”… Child emits “ah” and the child’s emitted response is reinforced.

The benefits and limitations of SET

Our experience has shown that employing SET is useful in establishing early verbal imitative responding. SET is used to establish other verbal operants as well. Very often however, the benefits of SET diminish as one moves from establishing simple echoics and teaching simple naming (naming of things in the world). However, its use for establishing more complicated linguistic abilities leads to echoic interference. For example, when a teacher asks the question, "Do you want a cookie?" and wishes to prompt an echoic "Yes", the instructor will say, “Do you want a cookie yes”. It is hoped that by using SET, combined with various stimulus fading procedures and prompt fading procedures, a youngster will eventually say,"Yes”, in the presence of the truncated antecedent, “Do you want a cookie?”. Unfortunately, getting to the desired response is not always easy. Let’s explore this a bit.

When considering the procedure, the first question one might ask, in reference to the above example, might be, “How can a child know to echo only ‘yes’, “Why wouldn’t the child echo the entire phrase? “Why not the last two words?” In fact, children can’t possibly know, and thus we often see what we call, ‘hanging echoes’. Therefore, when we say, “Do you want a cookie yes?” very may often children say, “Cookie yes” or “Want cookie yes” or even the entire uttered statement. This should not surprise us since there is nothing in what we say that differentiates the intended “prompt” from the intended ‘question’. There is no demarcation i.e., this part is the question you are to answer, and this part is the appropriate answer you are to provide. The verbal antecedent is fused as one continuous, undifferentiated stream of words. Any user of English could not make sense of what was said. It is not English. Any learner would not be learning English but would be learning VeeBee-ese.

Given this problem, the next question might likely be, “Why not simply teach a youngster to respond to the instruction “say”, so that children will know what to say and when to say it. Good question…and one that is frequently asked. The common response to this question is that saying ‘say’ often results in children echoing the word “say” in addition to the intended target for imitation. Therefore, the usual prescription is to not use a “say” instruction. A second reason for the use of SET is that, from the perspective of practicing ‘verbal behaviorists’, the procedure leads to some success in establishing rudimentary verbal operants.

While using SET may result in the accumulation verbal operants, it confounds efforts at teaching language

But, it must be pointed out, even if there is some success is obtaining and accumulating verbal operants, acquiring desired verbal operants by using SET can be hit or miss. Moreover, having verbal operants is not the same as having language. You see, “verbal behavior” it is not language. It is behavior. But language is not behavior. An utterance is behavior. What is uttered is not. It is language. (You don't have to take my word for it, just ask Skinner, 1957, p.2). Verbal Behavior accounts for 'controlling relations' in the behavior of the speaker. Language on the other hand is the practice a verbal community, which Skinner (1957, p.2) says,“has become remote from the behavior of the speaker.” Primary operants, as Skinner laid them out, describe specific behavior-environment relations; nothing more. Language is something different.

To learn a language is to learn the activities, practices, actions and reactions within characteristic contexts in which the rule governed use of words are integrated (Hacker, 2013). It is to learn a social technique. It is to learn to do things with words, the practice forms of language, such as asking, telling, naming, directing, promising, describing, explaining, cajoling, negotiating, refuting, refusing, agreeing, directing, correcting, teasing, comparing, contrasting, tattling, inviting, etc. To learn a language is to be able to manipulate symbols according to the rules for their use; to learn their meanings. It is to say things that for which there is a 'point'. Knowing this, we need to also ask, “Shouldn’t the approach driving ‘language intervention’ be consistent with a language based conceptual system? More specifically, an 'natural language-based' framework?

Tools for teaching language need to be 'at home' in a language-based conceptual scheme

To be able to make moves in language is not to have fixed responses determined by controlling antecedent stimuli. To understand a move in language is not to 'account for controlling relations', but to understand how what is said is consistent with what is done within a practice. For example, to answer a “why”question is to give a reason. There are an indefinite number reasons one could give to a ‘why ‘question. Answering a "where" question is bound up with place. Given this, it is inconceivable to imagine ‘generalized responses’ or ‘histories of reinforcement’ which would account for an unspecified number of reasons or places situated in an unspecified number of situations, circumstances or transactions bound up with a query.

Thus, the goals related to language learning for children with autism need to be 'at home' within the conceptual scheme of the thing which one is trying to teach... which for most of us working with children with ASD, it is to teach a language. To use 'tools' for language instruction that have a place within other conceptual schemes will likely clog up the works. This is the case with using SET. It goes without saying, that the tools one uses should not interfere in achieving your goals. The tools need to be sure in purpose and accuracy. With these requirements in mind…how does the use of SET hold up as a tool for language instruction?

Not well. First, encouraging (reinforcing) echoing in persons who may already manifest pathological echoing (echolalia), may result in increased echolalia. Second, the use SET actually confounds efforts at teaching a language as its use runs counter to conventions of use in ordinary language. It confuses as it violates the rules and renders efforts incoherent within a language scheme. SET does not clarify, ‘when to echo/imitate (and when not to) or precisely what to echo/imitate’ as would a common instruction, “say”. SET can’t provide the accuracy needed to tackle complex language goals. Examples of the imprecision of SET as are shown below:

1. Teaching greetings:

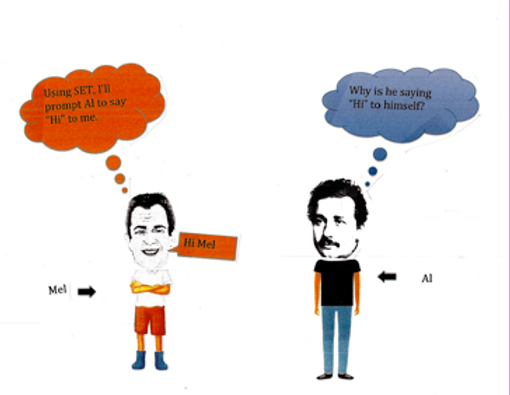

In this example (Figure I) , a teacher (Mel) attempts to teach a child, Al, to greet him.

Figure I

When viewing this sequence, one is left to consider whether,

1) These people live in a parallel universe where everything is said in opposites

2) This is a perfectly acceptable method for teaching someone to offer greetings since it results in the establishment of an echoic relation and comports with “the science”.

3) This is a very peculiar way of teaching someone to offer greetings.

The youngster is Al, the instructor is Mel. Using this strategy for teaching someone to greet someone violates conventions of ordinary language in which there is an agreed use of symbols that are used to refer. But since establishing verbal operants is the primary concern in an AVB based approach, using SET is fine, since its use satisfies the requirement of establishing verbal operants. Since some children do learn to produce the desired response/s, there would be no concern about its use. But eventually, this strategy ends up getting in our way, as language targets get mangled in the mix.

Now imagine, if the teacher, Mel, had decided to attempt reciprocal greetings. Mel would have said something like, “Hi Al Hi Mel”. This is common practice and while it may work for some children it’s a very confused and a confusing way of instructing children in the basic rules for greetings. There is nothing in this effort that clarifies for the child what they are to do, nor does it resemble anything in English. Wouldn’t it be much simpler and clearer to simply instruct a student using a “say” instruction? The sequence would look like this.

Teacher: “Hi Al, say “Hi Mel” and all conventions and the need for clarity are satisfied…and the rules when speaking English are maintained.

2. Teaching “Asking questions”:

In Figure II, the instructor wants to teach a youngster to ask a question. But, instead, the teacher is actually asking a question… even though what he says is intended as an echoic prompt.

Figure II

Now, assume, that in this case, the ‘ecohic prompt’, “What are you eating” is a question that child has learned to answer, in which case the child is likely to answer the question. Naturally, the child can’t know that the ‘question’ is actually an echoic prompt. Confusing, right?

The same problem exists when we want to teach children to give directions rather than follow them. For example, if I want a child to learn to tell me how to build a block structure, using SET I would say “Put the red block on the green block”. How could the child possibly know whether what I say is a ‘prompt’ to imitate what I say or a direction that they are to follow. There is no way. But eventually, children will need to learn how to direct others to do things and we will need to help them learn to do this.

3. Pronouns/ giving directions

Figure III

In Figure III, the instructor wants a child to say, “Throw me the ball”, and says, “Throw me the ball” intending to prompt the child to say the same thing. In this case, one sees immediately that basic deixic relations are disregarded. “Me” always refers to the speaker. In this case, when the speaker says, “Throw me the ball”, the instructor is telling the child to throw the instructor the ball. It can’t be any other way. This is how our language works. These words have a place in grammar (a la Wittgenstein) and mean things. Used outside of their agreed upon place is just incoherent. It seems only natural that as instructors of a language, our teaching conform to the practices within that language…that if we intend for children to learn a language/ that our language models correspond to the practices within that language. Can it be any other way? Would you try to teach chess expressed in the rules for checkers? To teach soccer according to the rules of baseball. Of course not...and even if you wanted to, it wouldn't be possible.

And to drive the point home, pronoun use is a fundamental feature of English. Learning to use them is complicated. Part of the challenge in learning to use pronouns is that they are contextually determined. There are many moving parts and learning to use them requires vigilant tracking across shifting speakers (you, they, he, she, Ralph, etc.) and listeners (I, We, they, she, he, Ralph, etc.) and requires ongoing changes in responses. We need to be as precise as possible when instructing children in how they work. At a minimum, a child needs instruction that doesn’t confuse and which operates within the rules of the language one is trying to teach. Using SET fails in this effort.

Adding to this difficulty is the common assertion that pronouns are things we 'tact'. This lacks sense. First, saying this does not comport with the definition of what qualifies as a tact. Pronouns do not exist in the world. They are not events, objects or properties. (Such as Skinner identifies things that are 'tactable'.) Pronouns exist in language. Just as "animals" exist in language. There are no "animals" in the world, although there are snakes, bears, turtles, elephants, tigers, snakes, ants, worms, etc. in the world. Second, and most important, we use pronouns. To learn a language is to learn 'use' of words and expressions according to convention.

The use of SET has its place within a ‘verbal behavior’ approach and has very limited utility in a language based instructional scheme. I need to emphasize, Skinner’s “Verbal Behavior” and derived applications are not about language (Skinner, 1957 p.2). Language and VB are very different conceptual schemes and should not be crossed, although they are, ubiquitously. (e.g., Sidener, 2010) Using SET, beyond establishing the rudiments of vocal imitation just confuses. Children need to learn when to say what we ask them to say by teaching them to say what they are directed to: To say “x” only when instructed to say“x” by using the instruction, “say”.

There are a few strategies we employ in order that child learn what the instruction “say” means:

1) Whispering the instruction “say” and punching the words to be said is one way.

2) Whisper the instruction “say” and slightly delaying the words to be said is something else to try.

3) Present nonsense words either preceded by the instruction, “say” or without. For example, “PLOOKY PLOOKLY” vs. SAY “PLOOKY PLOOKY”.

4. From the previous exercise, we will move to a “say vs “do” program. In this case, an instruction to ‘clap’ is interspersed with an instruction to say “clap .” i.e, say the word only if you hear the word “say”, otherwise perform the corresponding action.

These strategies are not mutually exclusive and can be combined…but require meticulous teaching procedures. See what works. If a child learns how to follow this basic and essential instruction, teaching children answer questions, use pronouns and the practice forms such asking, directing, explaining, telling, etc., is in reach.

Summary and Conclusions:

Our experience has shown that using SET is a useful tool for establishing early verbal imitative behavior. It is commonly used for establishing tacts, mands and intraverbals. But its use beyond establishing early verbal imitation is clumsy and is a poor choice for language instruction. First, it may increase pathological echoing in children who already demonstrate such tendencies. Second, as a tool for teaching a language, its use violates conventions of use, confuses rather than clarifies what is required of children for when and what to say. Such problems significantly hamper our ability for teaching basic linguistic abilities and certainly more advanced abilities (asking questions, pronoun use, giving directions etc.).

By establishing a conditional instruction, say what I tell you to say, (the instruction “say”) will allow language-based instructional efforts to precede and succeed for far more children. We have found that by careful and creative contingency and prompting arrangements (Say vs. do) it is easily possible to establish “say” as a conditional instruction.

Establishing its use clarifies for children when to say and when not to say what someone else says. The ultimate question is whether clinicians should be satisfied with establishing only verbal operants. If so, then using SET is fine, since it is consistent within a VB paradigm despite its significant limitations and resulting confusion. On the other hand, if clinicians hope that children learn a language, SET needs to be put aside early on and replaced with a ‘say’ instruction if children are to be given a better chance at learning a language.

References

Hacker, P.M.S. (2013). The intellectual powers. A study of human nature. Wiley.

Lund, S. K., & Schnee, A. (2018). Early intervention for children with ASD: Considerations. Infinity.

Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. Copley Publishing Group.

Shane, Joseph, "Increasing Vocal Behavior and Establishing Echoic Stimulus Control in Children with

Autism" (2016). Dissertations. 1400.

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1400

Sidener, T. (2010), What is Verbal Behavior? Association for Science In Autism Treatment Vol. 7 No. 3.